Introduction

In the movie “Minority Report” Tom Cruise stars as Precrime Chief John Anderton who heads a specialized police department that apprehends criminals using foreknowledge provided by three psychics called “precogs”.

The idea of course is that psychics are able to predict when someone is going to commit a crime before they’ve actually done it, and therefore the mens reus, or intent alone, is sufficient to secure a conviction.

Fortunately, most legal systems do not operate this way.

Instead both the mens reus or intent to commit a crime needs to be combined with the actus reus or the actual criminal act, to constitute the crime alleged.

This is what makes the process of “blacklisting” blockchain addresses so challenging.

In this case study, we examine the stablecoin issuer Tether’s track record of “blacklisting” blockchain addresses, and provide data that was also supplied to the Wall Street Journal, to provide a data-driven overview on the efficacy of “blacklisting”.

What is “blacklisting”?

There are two types of blockchain address “blacklisting”.

Freezing

“Freezing” is when crypto-assets or stablecoins in a blockchain address can no longer be transferred after the “blacklisting” has been implemented, usually by the centralized issuer of that crypto-asset or stablecoin.

One common misconception is that when a blockchain address has been “blacklisted” all of the crypto-assets and stablecoins in that blockchain address are “frozen” and can no longer be transferred out of the blockchain address.

However, only the centrally-issued crypto-assets or stablecoins with a “blacklisting” function can be “frozen” by their issuer, while the blockchain address can continue to transact in other crypto-assets and stablecoins not subject to such “freezing.”

For instance, the stablecoin USDT is centrally-issued by Tether, and when a blockchain address is “frozen” or “blacklisted” by Tether, only the stablecoin USDT can no longer be transferred out from that blockchain address.

If someone attempts to transfer USDT out of a blockchain address “blacklisted” by Tether, when their blockchain address makes a call to the smart contract operated by Tether, the administrative functions controlled by Tether prevent the USDT transfer.

However, other crypto-assets that are not USDT are not prevented from moving freely into and out of a blockchain address “blacklisted” by Tether.

For instance, ether, the native crypto-asset for the Ethereum blockchain, can continue to be transferred into and out of a blockchain address even after the address has been “blacklisted” by Tether.

Notification

Another type of “blacklisting” involves notification, usually by national or state authorities, that certain blockchain addresses are either subject to sanctions, or identified to be involved in illicit activity.

The Office of Foreign Assets Control for instance states clearly in its “blacklisting” of blockchain addresses that the provision of that information is intended as a convenience, and not intended to “be exhaustive”#.

While a national or state authority may “blacklist” a blockchain address, crypto-assets and stablecoins in that “blacklisted” blockchain address can still be freely transferred unless the crypto-asset or stablecoin issuer has measures in place to “freeze” the asset or stablecoin, and does so.

How much “freezing” does Tether do?

It is important to note that many crypto-asset issuers do not design their products to cater for “freezing”.

Blockchain networks are generally intended to facilitate permissionless transactions, with no central authority to block transfers. As such, the vast majority of crypto-assets are generally not susceptible to being “frozen”.

Nevertheless, centralized stablecoin issuers, such as Tether, do have in place systems to “freeze” their crypto-assets in specific blockchain addresses, but this usually only happens after those blockchain addresses have been identified as involved in illicit activity.

Number of Blockchain Addresses “Blacklisted” by Tether Since 2018

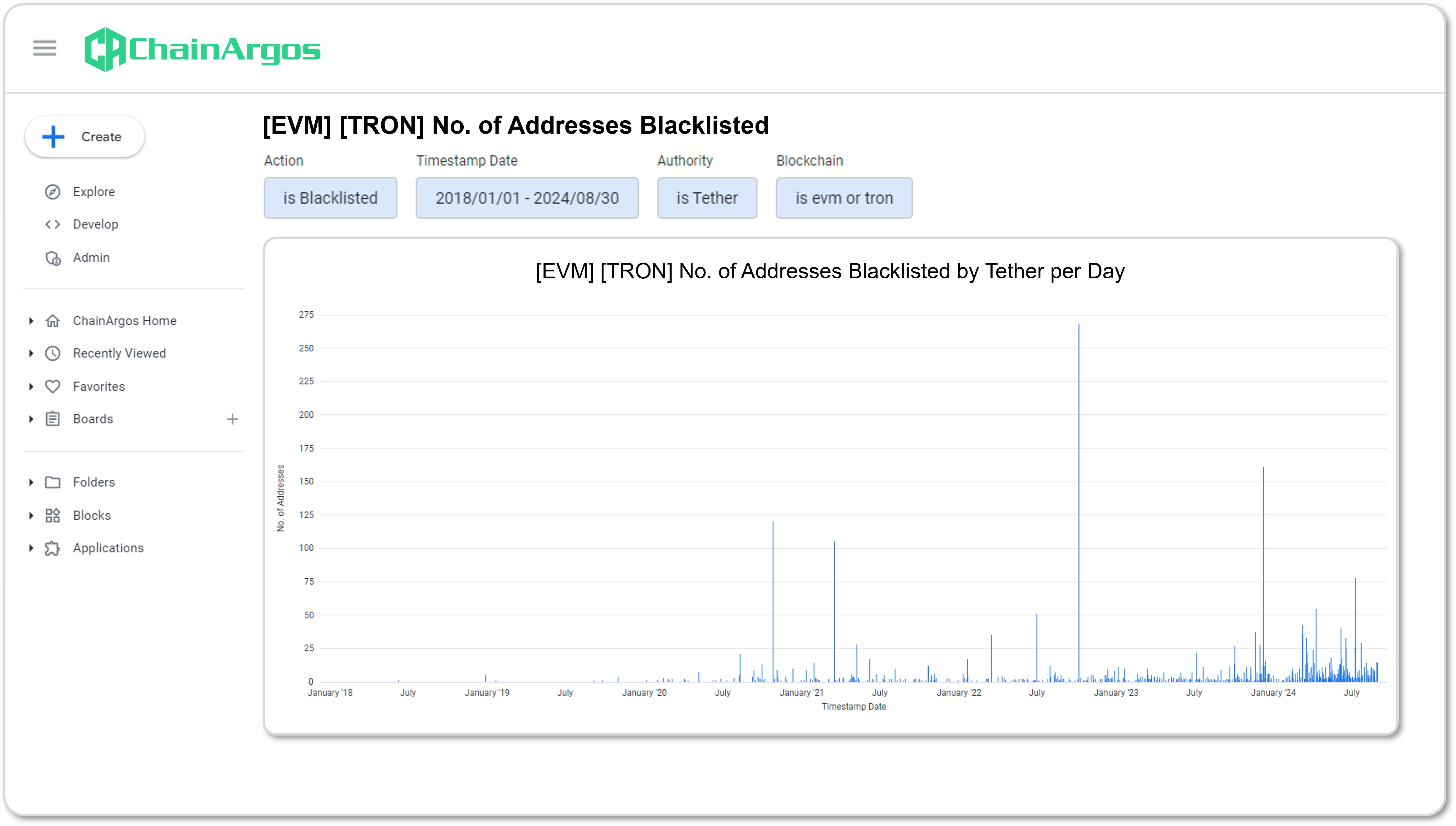

Figure 1. shows the number of blockchain addresses “blacklisted” by Tether between January 1, 2018 and August 31, 2024 on the Ethereum and TRON blockchain networks by date.

Figure 1. No. of Blockchain Addresses Blacklisted by Tether by Date on the Ethereum and TRON blockchain networks.

The chart in Figure 1. provides some interesting observations.

For instance, the largest number of blockchain addresses “blacklisted” by Tether was October 6, 2022, when 268 blockchain addresses were “blacklisted.”

And while Tether has “blacklisted” blockchain addresses from time to time, the “blacklisting” activity really picked up in 2024.

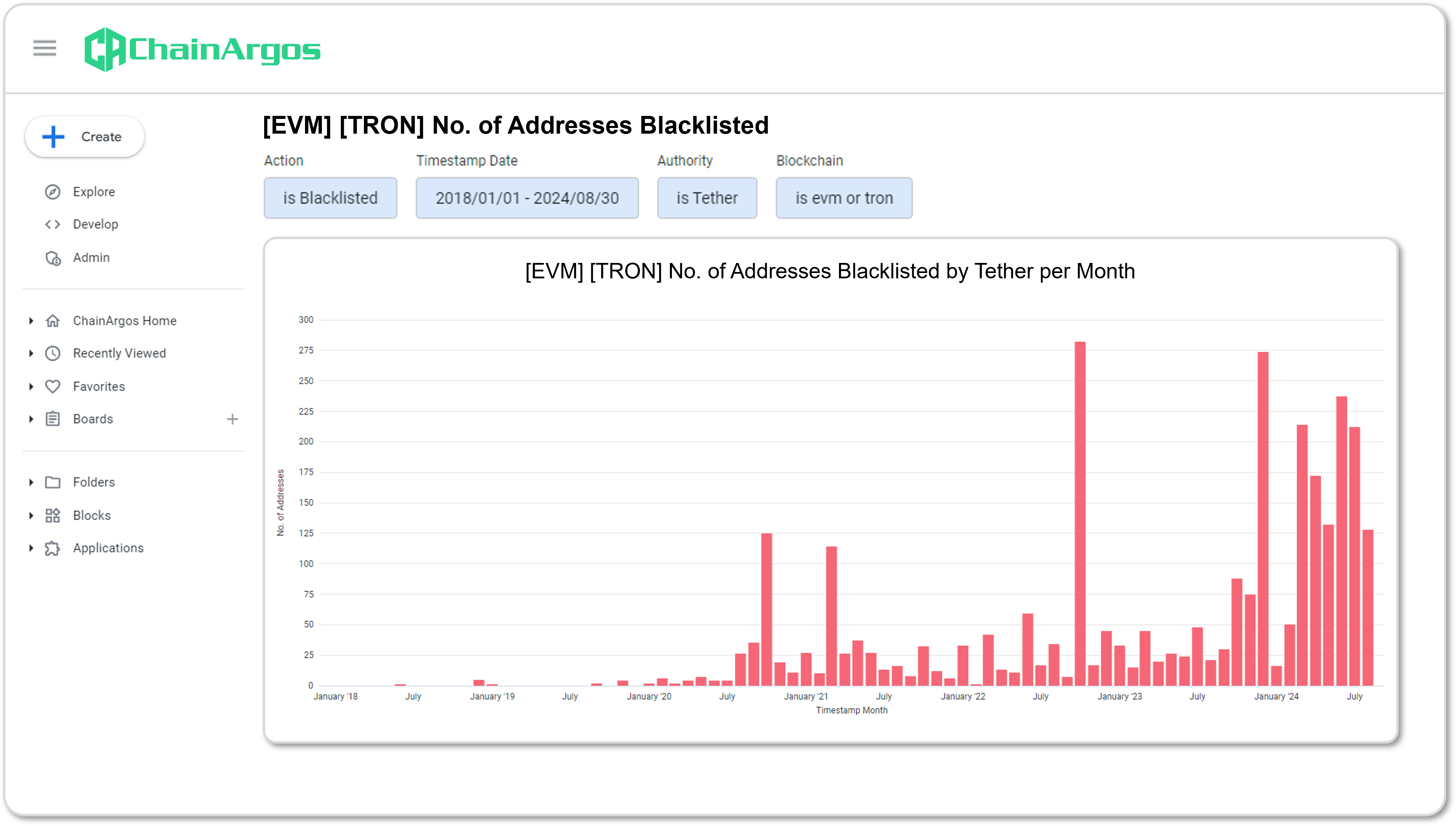

The following chart in Figure 2. shows the number of blockchain addresses blacklisted by Tether monthly, from January 1, 2018, to August 31, 2024.

Again, October 2022 stands out, where a total of 282 blockchain addresses on the Ethereum and TRON blockchain networks were “blacklisted” by Tether.

Figure 2. No. of Blockchain Addresses Blacklisted by Tether by Month on the Ethereum and TRON blockchain networks.

It is one thing to “blacklist” a blockchain address, but transaction data seems to suggest that it is far more difficult to trap supposedly illicit USDT flows through that blockchain address – the proverbial closing of the barn door after the horse has already bolted.

How much Tether was “frozen”?

The amount of USDT that effectively gets caught when a blockchain address is “frozen” varies significantly from blockchain to blockchain.

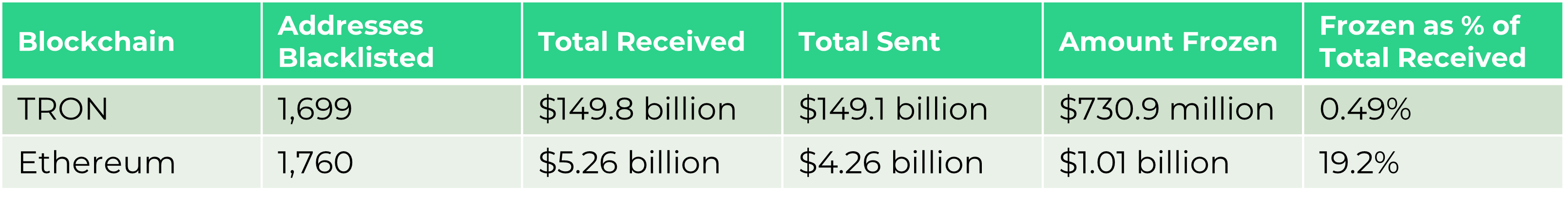

Blockchain network transaction data from the Ethereum and TRON blockchain networks between January 1, 2018 and August 31, 2024, is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Tether Blacklisting figures between January 1, 2018 and August 31, 2024.*

In Figure. 3, the sheer volume of USDT flowing through blockchain addresses “blacklisted” by Tether on the TRON blockchain network completely dwarfs the USDT volumes through the Ethereum blockchain network.

That there is more USDT flowing through blockchain addresses that are “blacklisted” by Tether on the TRON blockchain network should come as no surprise, as in general, there are far more transactions for USDT on TRON than on Ethereum.

Transaction fees are significantly lower for USDT on TRON than on Ethereum, which is why many choose to transact USDT on the TRON blockchain network, instead of Ethereum.

Regardless, the amount of USDT Tether has been able to “freeze” on different blockchain networks also differs dramatically.

On the TRON blockchain network, Tether only managed to “freeze” around 0.49% of all inbound USDT to “blacklisted” blockchain addresses, meaning a whopping 99.51% of possibly illicit USDT made it through.

Whereas Tether has had far more success “freezing” USDT on the Ethereum blockchain network, with almost 1 in 5 USDT flowing into “blacklisted” blockchain addresses successfully “frozen”.

The observations are not intended to be a criticism of Tether, but rather to highlight the difficulty involved with trying to “freeze” illicit fund flows in a permissionless environment.

* Please note that the Wall Street Journal data covers the period from January 1, 2018 to June 30, 2024. In this case study, we have expanded the time frame from January 1, 2018 to August 31, 2024. USDT values have not been rounded up or down and totals are inexact. The “Total Received” and “Total Sent” refer to USDT totals received by and sent from blockchain addresses ultimately “blacklisted” by Tether.

Does transaction behavior change before “blacklisting” by Tether?

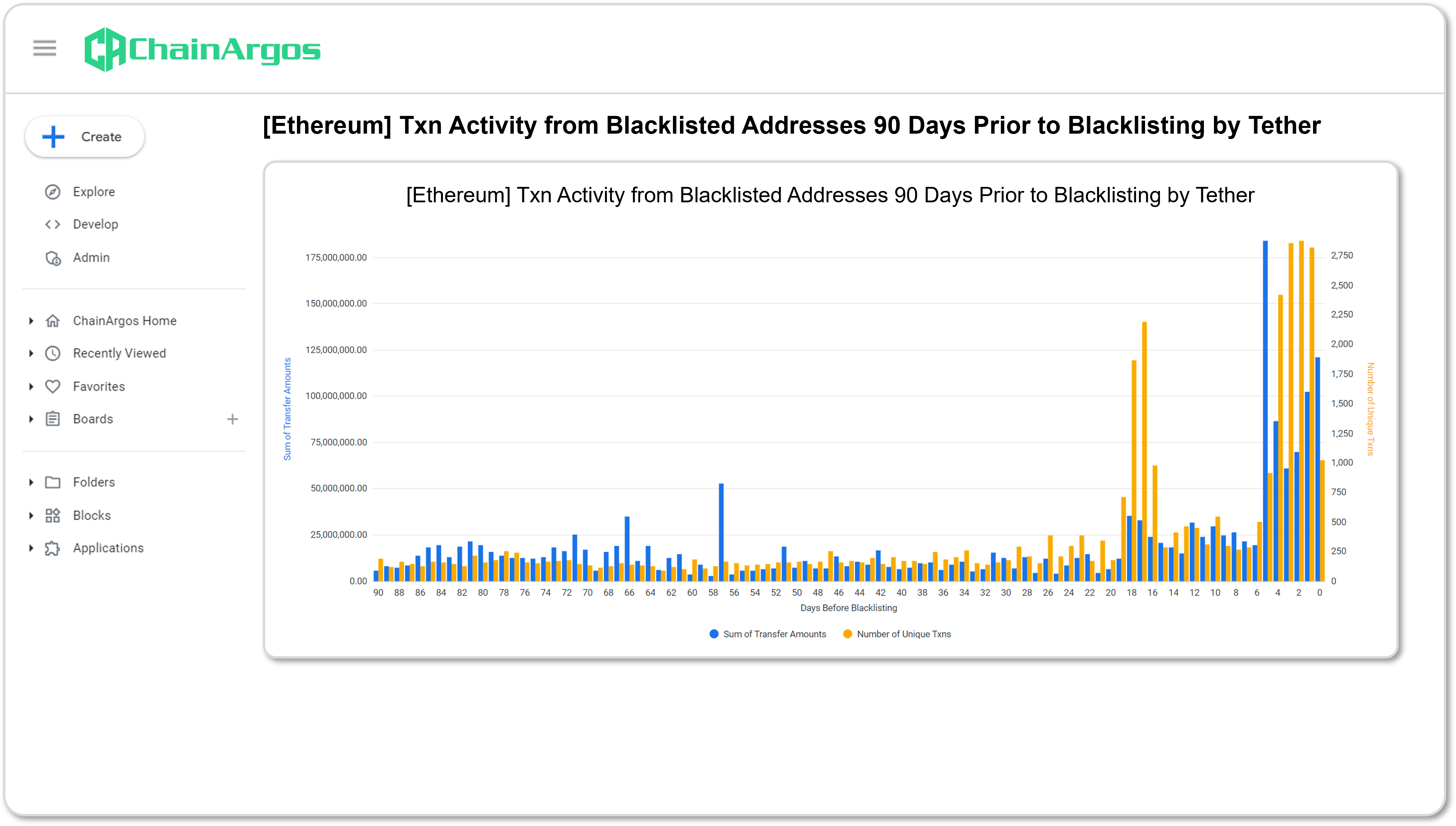

Figure 4. takes a look at USDT flows out of blockchain addresses up to 90 days before they are “blacklisted” by Tether on the Ethereum blockchain network.

It is clear that in the week or so before a blockchain address is “blacklisted” by Tether, there is both an increase in the number of unique transactions, as well as the volume of USDT being transferred out.

Figure 4. Sum of USDT Transfers and No. of Unique Transactions to 90 days before “blacklisting” by Tether on the Ethereum blockchain network.

In Figure 4., the yellow bars represent the number of unique transactions from a blockchain address on the Ethereum blockchain network that will eventually be “blacklisted” by Tether. The blue bars represent the sum of transfer amounts of USDT.

“Unique transactions” means the transaction count. There is a significant increase in transactions in the week just before the blockchain address is “blacklisted” by Tether.

It is obvious that on the Ethereum blockchain network, blockchain addresses that face imminent “blacklisting” see a significant increase in both amounts and unique transactions just before their USDT is “frozen” by Tether.

This in no way implies any impropriety or information leakage on the part of Tether to these blockchain addresses before their USDT is “frozen.”

For instance, citizens of a city fleeing ahead of an air strike, doesn’t necessarily imply that news of an imminent attack has been leaked, but rather a general awareness that dangers lay on the horizon in a time of conflict.

It’s entirely possible that owners of these blockchain addresses ultimately “frozen” by Tether were aware of impending law enforcement action and were moving funds as quickly as possible to prevent them from being lost to “freezing”.

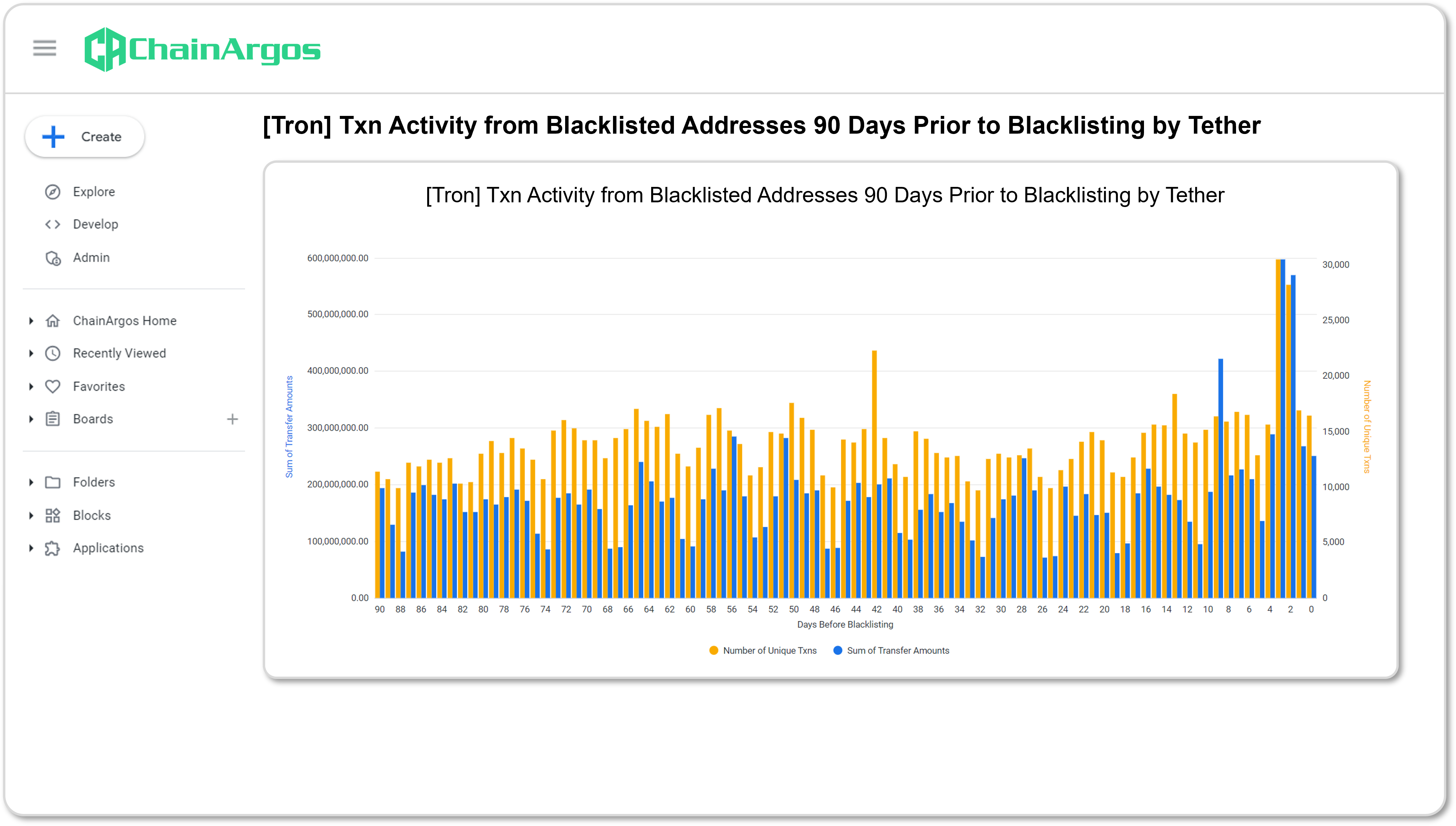

Figure 5. examines USDT transaction activity 90 days before Tether “freezes” these blockchain addresses on the TRON blockchain network.

Again we see the same sort of uptick in transaction volumes and unique transactions, just prior to “blacklisting” by Tether on the TRON blockchain network as was observed on the Ethereum blockchain network.

Figure 5. Sum of USDT Transfers and No. of Unique Transactions to 90 days before “blacklisting” by Tether on the TRON blockchain network.

Can we do better?

The data reviewed suggests that if the goal of “blacklisting” is to stop the flow of illicit funds, then “blacklisting” may not be the best way to do it.

While it may be possible for Tether to pre-emptively and pro-actively “freeze” blockchain addresses it suspects are involved in illicit activity, or will potentially be involved in illicit activity, doing so reliably assumes Tether has access to “precogs”.

The problem is exacerbated by the fact that it’s trivial for nefarious actors to create new blockchain addresses, staying one step ahead of “blacklisting” in a never-ending cat-and-mouse game that issuers like Tether are ill-equipped to win.

This issue isn’t as pronounced in the traditional financial system as banks are heavily regulated, licensed entities, which generally have in place frameworks that are designed to prevent and stop illicit fund flows.

For instance, it’s not trivial to open a single bank account on one day, let alone multiple bank accounts by the same individual on a single day.

While some may argue the ability to open bank accounts quickly is disadvantageous from the perspective of efficiency, there are clearly advantages in the context of compliance with existing regulations.

More importantly, banks and financial institutions operate in a highly “permissioned” environment, where transfers require intermediaries that act as chokepoints, to prevent uncontrolled illicit flows.

However, crypto-assets and stablecoins operate on “permissionless” blockchain networks, with no central intermediaries.

No system is perfect of course.

But the empirical evidence is compelling that a system of “permissionless-access with backward-looking blacklisting” is meaningfully ineffective in stopping, or trapping, illicit funds. Further, it is clear this is not a minor shortcoming that can be fixed with incremental technical upgrades but rather an in-built feature of richly programmable permissionless systems that necessitate compromise+.

In this context regulators, policymakers, and law enforcement should consider whether the current permissionless system’s performance merits official approval or if a different approach is required.

+For a more detailed discussion on compliance frameworks in permissionless systems, please see Charoenwong, Ben and Kirby, Robert M. and Reiter, Jonathan, Decentralized Finance and Financial Regulation: Limits On Mutable Turing Machines (March 6, 2024).

Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4597651 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4597651