Introduction

In an earlier case study, we discussed whether Usual USD’s USD0 and USD0++ products were a way to circumvent the European Union’s flagship crypto-asset law, the Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (“MiCA”).

In our previous case study, we questioned how USD0 and USD0++ could be MiCA-compliant given it appeared to be a transparent attempt to set up an interest-bearing stablecoin (USD0++) usable in the European Union.

- USD0++ cannot be licensed under MiCA (it pays interest which MiCA prohibits);

- USD0++ is issued by a French company (France is part of the EU and therefore MiCA applies);

- USD0 could potentially be MiCA-compliant, but is not currently; and

- USD0’s primary (possibly only) use case is as a token to be staked to create USD0++ (which pays interest).

For this case study, we’ll set aside Usual USD’s potential regulatory issues and examine design decisions that led to USD0++ slipping its “peg” in early January 2025 and how investors and regulators could have seen it coming.

What are USD0 and USD0++?

By way of a quick recap, USD0 is a dollar-based stablecoin backed by the USYC token, which is itself backed by US Treasury Bills, so market participants can be relatively confident USD0 ought to hold its $1 peg.

Legal issues aside, USD0 appears for all intents and purposes to be a functional dollar-based stablecoin.

Enter USD0++, a “composable token that represents staked USD0, functioning like a liquid savings account” where the interest paid from this staking scheme is paid in USUAL tokens, a token whose “value increases with the Total Value Locked (TVL)” in the USUAL protocol.

USD0 is a stablecoin that pays no interest even though USYC which backs USD0 does.1 So someone or something somewhere is earning interest on USD0 held on-chain because the USYC backing USD0 is earning interest.

Usual USD issues USD0 and one plausible explanation is that Usual USD simply keeps the interest, a not uncommon practice for many stablecoins.

Another plausible explanation is that the total interest on all the USYC backing USD0 is shared among whoever stakes USD0 to get USD0++.

In that case, the interest generated from USYC would effectively go to USD0++ holders. If only a small fraction of USD0 in circulation is staked, then USD0++ holders could expect to receive a very high yield.

As documented earlier, most USD0 ends up staked for USD0++. This means USYC interest mostly ends up with USD0++.

While this arrangement is messy and the overall design space is huge, empirically USD0++ is a relatively straightforward product given USD0 is not used for much outside of staking for USD0++.

1 USYC is redeemable at an escalating price over time. This is how holders collect interest. See, for example, https://www.coingecko.com/en/coins/hashnote-usyc

Issues With USD0 and USD0++ Priced at $1?

To reiterate, USD0 is a dollar stablecoin that pays no interest. USD0++ is related to USD0 in that a market participant receives USD0++ (a token that pays interest) when they stake USD0 with the USUAL protocol.

Now zoom out a minute and consider that if USD0 is worth $1 and pays no interest and you can swap it 1:1 for USD0++ (which does pay interest), instinctively, something should feel off.

We previously noted that “USD0’s primary use [is] for staking to receive yield from USD0++,” a fact backed by on-chain transactions which show that the #1 thing market participants do with USD0 is stake it for USD0++.

That behavior is perfectly rational because as long as USD0 and USD0++ are interchangeable at the price of 1:1, a rational investor would necessarily prefer USD0++ (which pays interest) for USD0.

So why would USD0 and USD0++ trade at the same price when USD0++ is simply USD0 with yield?

No. USD0++ is not simply USD0 with yield.

It’s important to remember that USD0++ is staked USD0 and the USD0 staking program locks that staked USD0 for 4 years!

USD0++ holders are paid yield, but they cannot unlock the USD0 they’ve staked for years!

It would therefore stand to reason that USD0 and USD0++ shouldn’t trade at the same price, yet the two tokens were artificially held to the same peg to presumably encourage early adoption.

Usual USD initially allowed people who staked USD0 to break their staking agreement for free.

This created the transparently unsustainable situation where USD0 and USD0++ were interchangeable for 1:1, except one token paid yield while the other didn’t.

As expected, and evidenced by blockchain transaction data, everyone loaded up on USD0 and did what it was designed for, staking USD0 for USD0++.

In Usual USD’s defense, the team made clear that USD0++’s 1:1 equivalence with USD0 was a short-term arrangement and stated that “USD0++ is not a stablecoin.”

The Usual USD team also declared that “in early 2025 we will remove the 1:1 exchange with USD0.”

But this being crypto, nobody paid attention to these disclaimers and apparently few market participants read the fine print.

The legion of “DeFiant” yield-hungry market participants just continued to create USD0 and staked it for USD0++ secure in the (mistaken) belief that USD0++ would maintain its 1:1 peg with USD0.

That crypto-asset investors would fail to read the fine print on a new stablecoin promising yield without having to “lock” your tokens isn’t altogether surprising.

It’s perhaps even less surprising that an unregulated EU-domiciled stablecoin would run into issues.

The “De-Pegging”

On January 10, 2025, Usual USD (as promised) removed the 1:1 exchange rate between USD0 and USD0++ replacing it with a mechanism that accretes the price of USD0++ upwards from $0.87 to $1 over 4 years of staking.

This unsurprisingly caught many yield-seeking investors unawares and the price of USD0++ to gap down.

Figure 1. Chart showing the price of USD0++ dropping dramatically from $1 after the re-pricing was announced.

Essentially everyone who bought USD0++ at $1, expecting it to be directly swappable with USD0 appeared as if they had been “rugged” (to use industry parlance).

But at the same time, it was clearly wrong that USD0 and USD0++ were 1:1 ever to begin with, a fact that has nothing to do with regulation.

How can a token (USD0) which bears zero interest be exchangeable at the rate of 1:1 with a token that bears interest (USD0++) but has a 4-year lock-up?

While the interest paid on USD0++ may mitigate how far below $1 it trades, there’s no reason for the price of USD0 and USD0++ to both be $1.

For instance, the price of USD0++ may be $0.90 and factoring for interest may see it sell for $0.95, but this is a floating price.

Even where the redemption discount is 10 cents and the interest accrual exactly offsets that discount with 10 cents of value and the price of USD0++ is $1, that USD0++ is still a floating price, not a peg.

Market participants will change their assessment of what the price of the interest-bearing token is relative to the non-interest bearing stablecoin from time to time and this is precisely what happened when the artificial peg was removed.

Understanding the Value of USD0++

USD0++ has four components of value:

- The value of USD0 (the underlying stablecoin staked for USD0++)

- The value of USD0++’s interest stream

- Subtract the cost of having USD0 tokens locked for 4 years

- Adjust for any early-redemption recall fees or similar fees

Putting that together using hypothetical values makes it easier to visualize:

Although USD0 is worth $1, even if the projected value of USD0++’s interest stream is $0.05, the price of USD0 needs to be discounted by the need for USD0 to be locked for 4 years.

The price of USD0++ also needs to be adjusted to cater for early redemption penalties when a USD0 stake is removed any time before the 4-year maturation.

The locking of staked USD0 is why USD0++ should have been expected to trade at a discount to USD0 and the absence of any discount should have alerted market participants that all was not right.

In a simple fixed deposit mechanism, the interest paid on that fixed deposit is at the maturity of the term and there are penalties for early redemption.

Investors are compensated for not having the ability to move their money from the yield paid at the end of that fixed deposit term.

That anyone could swap USD0 with USD0++ at 1:1 ought to have been viewed skeptically from the beginning.

Instead of asking how this was possible, market participants instead chased yield and this can be seen when USD0++ poured into Morpho after USD0++ slipped from its $1 price.

Figure 2. Table showing the primary recipients of USD0++ in the aftermath of the de-pegging event was Morpho, another yield-generating protocol.

Everyone with a leveraged long position on USD0++ on Morpho was liquidated and suffered a significant loss, and much of the action on Morpho was not orderly unwinding, but panicked or forced liquidations.

Most USD0++ post-de-pegging has been deposited to or withdrawn from Morpho, another yield generating protocol.

Figure 3. Table showing the primary senders of USD0++ in the aftermath of the de-pegging event was also out of Morpho, another yield-generating protocol.

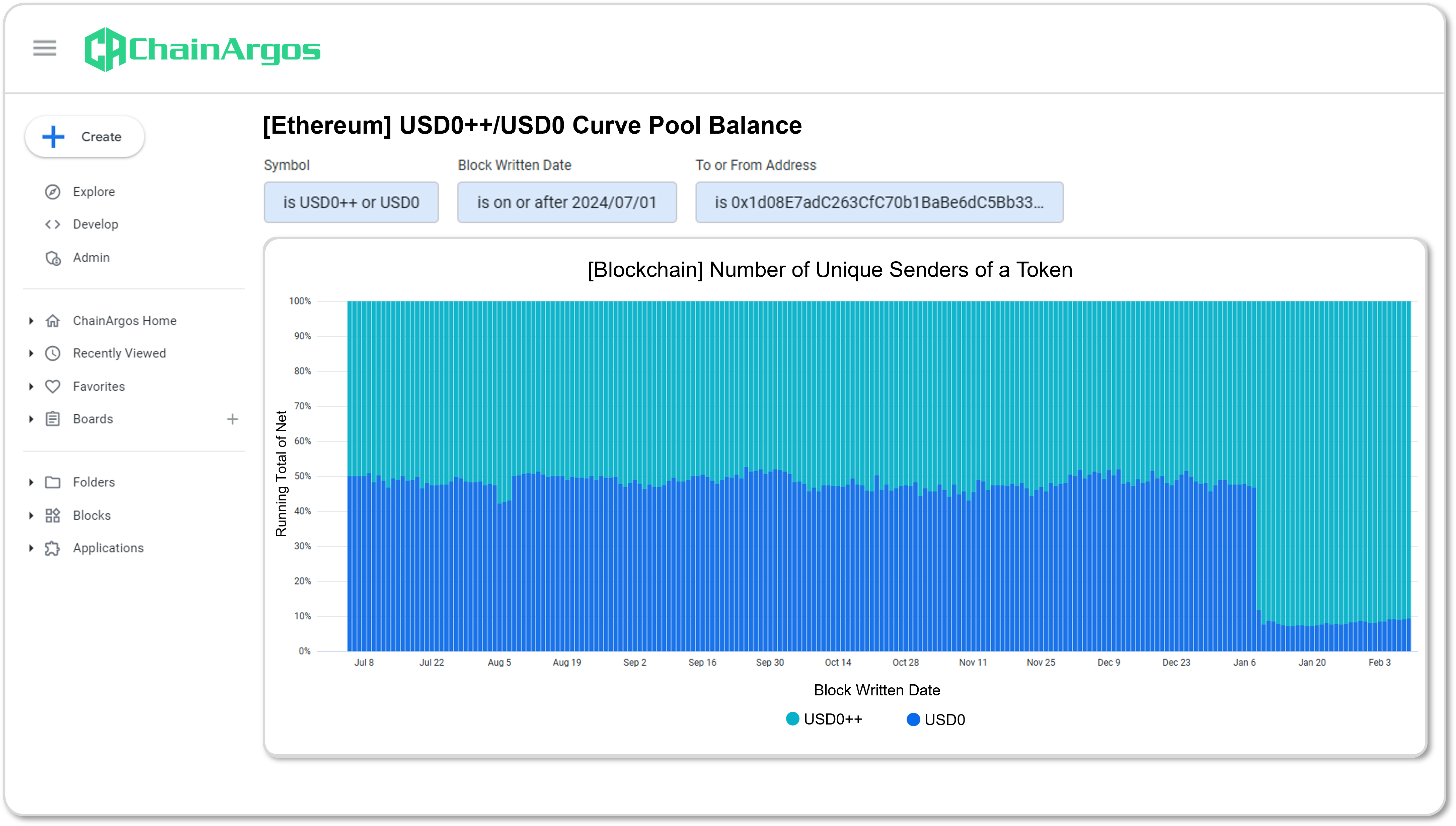

Figure 4. Table showing the sudden imbalance in Curve USD0++/USD0 pool that saw a removal of USD0 from the pool and USD0++ being left behind in the pool.

The same phenomenon was seen in the Curve pool when the balance in the USD0 and USD0++ pool on Curve gapped down in the repricing of USD0++.

As you can see from the chart pattern in Figure 4., where the belief was USD0 and USD0++ were exchangeable at the rate of 1:1, the Curve pool for USD0 and USD0++ maintained a fine balance close to 50:50.

But the minute that artificial peg was removed, market participants immediately decided that USD0++ was not worth the equivalent of USD0, removing USD0 liquidity from the Curve pool and leaving the less “valuable” USD0++ behind.

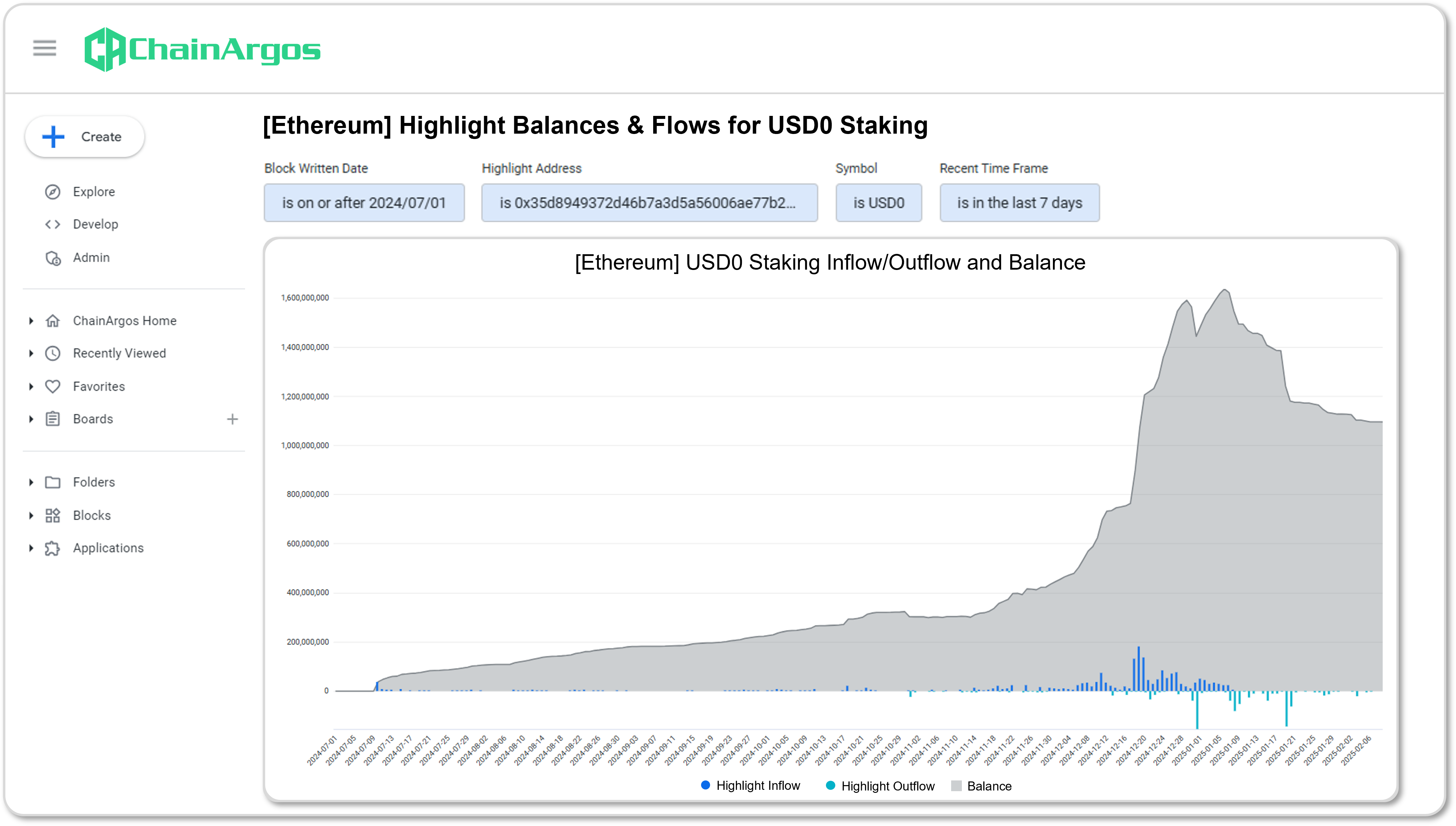

We can also see the significant drop off in the balance of staked USD0 once USD0++ was no longer fixed by Usual USD to be swapped for $1, as observed in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Chart showing the amount of USD0 staked over time (gray) the USD0 inflows (dark blue) and USD0outflows (light blue) from the USUAL Protocol staking program. A significant drop can be seen after the 1:1 exchange rate for USD0:USD0++ was no longer artificially supported.

For the most part there is little to no USD0 un-staked before USD0++ was re-priced, after which a steady stream of USD0 was un-staked.

Before the USD0++ repricing, there was a long steady stream of USD0 staked for USD0++, with a sudden uptick just before USD0 and USD0++’s 1:1 interchangeability ended.

USD0++ balances grew incrementally from its launch in July 2024 to December 2024, reaching over $500 million before a sudden and sharp uptick in USD0 staking, followed by the rule change.

That behavior looks suspicious to say the least.

Lessons Learned

1. Artificial Pegs Will Slip Eventually

Whatever the reason, USD0 and USD0++ price equivalency was an artificial peg that the market would not have naturally sustained.

Without Usual USD forcing a mechanism that ensured USD0++ could be exchanged for USD0 at the rate of 1:1, the market quickly decided the 4-year lock-up hurt the price of USD0++ more than USD0++’s interest accrual helped.

Such a determination by market participants is entirely reasonable and rational because money locked away for four years is not the same as money in your hands to do as you wish now.

As they say, a “bird in the hand, is worth two in the bush,” or such other value as market participants decide.

2. Identifying Hidden Pockets of Value

At the time this case study was prepared, USYC, the token backing USD0, was trading at about $1.08 (USYC is an interest-bearing token). This suggests there is value in the system somewhere for USD0 at a price above $1, but market participants need to understand the relevant mechanisms to determine what that price is.

It is not safe to rely on a 1:1 guarantee, especially where that guarantee itself appears irrational and unsustainable.

It’s also helpful to have tools to monitor all the relevant metrics when it comes to stablecoins such as USD0, and its closely related yield-bearing counterpart USD0++.

From keeping tabs on Curve pool balances for USD0++ and USD0, to monitoring the net flows of USD0 to the USUAL protocol staking contract, there are plenty of places to keep a close eye on how USD0++’s price could be affected.

Even though market participants could not have known the exact moment the Usual USD team was no longer going to support the artificial exchange rate mechanism for USD0 and USD0++, they could have seen the sudden uptick in USD0 outflows from the USUAL protocol, when there were no significant outflows prior.

By knowing the right measures to monitor, market participants could have saved themselves from considerable losses.

3. Beware of Unexpected Regulatory Intervention

While the entire Usual USD setup appears to be an attempt to dodge regulations such as the EU’s MiCA, this does not mean that regulatory enforcement will be imminent or even forthcoming.

There were plenty of market participants who assumed without reading the fine print that USD0 would be swappable for USD0++ at the rate of 1:1 indefinitely.

Market participants who bought USD0++ on this assumption would have been saddled with considerable losses and this could be the catalyst that spurs greater regulatory scrutiny.

Both USD0 and USD0++ are issued by French entities and USD0++’s re-pricing occurred in January 2025, well after MiCA was in force.

Whether the disclosures made by Usual USD for both USD0 and USD0++ were adequate under both MiCA and French law are questions French authorities will need to consider.

None of this is to say that schemes such as Usual USD ought to be shut down.

But more needs to be done by both market participants and regulators to ensure a greater awareness of not just the opportunities, but the risks associated with such schemes as well.