Introduction

As the number of financial institutions catering to stablecoin issuers grows, it’s more important than ever to understand how financial services can be provided to this growing customer segment safely.

In this case study, we examine some of the challenges facing financial institutions catering to stablecoin issuers, understand the idiosyncrasies of stablecoins issued on multiple blockchains, and explore the tools available to manage risk.

We’ll look at crypto-asset exchange Binance’s BUSD stablecoin product and explore what led to its shutdown and understand on-chain transaction data that needs to be monitored by financial institutions.

By identifying risks and understanding how to both monitor and mitigate such risks, financial institutions can be better positioned not just to cater to stablecoin issuers, but also gain a more thorough appreciation of the operating environment.

At the end of this case study, readers will:

- understand how to manage risks associated with providing financial services to stablecoin issuers;

- know how to handle stablecoin issuance and redemption exercises and reconcile those with on-chain stablecoin activity; and

- appreciate how blockchain intelligence can be used to develop effective monitoring and compliance frameworks when working with stablecoin issuers.

What are stablecoins?

A stablecoin is a digital token issued on a blockchain intended to maintain a stable value and is typically pegged to a national currency, with the US dollar being the most popular.

In the early days of crypto-assets, traders needed a place to park funds while trading in and out of more volatile tokens such as bitcoin, with fiat currency transfers taking too long.

It was from this demand for a stable token to park funds that stablecoins were born.

While there are many different types of stablecoins, the ones most relevant to financial institutions are those pegged to a major national currency such as the US dollar and backed by a reserve of assets, usually short-term government securities.

One common misconception is that stablecoins are almost exclusively backed by cash deposits in bank accounts, but this is rarely the case.

Cash deposits in bank accounts are generally only insured to certain maximums and should a bank experience a failure, a stablecoin whose cash deposits are at that failed bank may experience difficulties in maintaining its pegged value.

In the United States, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (“FDIC”) insures deposits only up to a maximum of US$250,000 if an insured bank fails.

Given that stablecoin issuers typically have billions of dollars’ worth of stablecoins in circulation, bank deposits alone are unsuitable to serve as reserve assets for a stablecoin.

For instance, Circle Internet Financial, issuer of the USDC stablecoin, had US$3.3 billion in cash reserves held with Silicon Valley Bank (“SVB”) at the time of that bank’s failure, causing its USDC stablecoin to slip its peg.

Had it not been for US government intervention to shore up SVB, over 8% of USDC’s reserve assets were at risk of being lost in the collapse, with the USDC stablecoin unlikely to have been able to maintain its pegged valued.

As such, many stablecoin issuers typically hold a mix of different assets on top of cash deposits at financial institutions, including short-term US treasuries, commercial paper and other assets of varying liquidity.

It is this demand for a range of financial products that has many financial institutions salivating at the prospect of serving stablecoin issuers as an emerging source for growing fee income.

However, the opportunities provided by stablecoin issuers are not without risk, including idiosyncrasies specific to blockchain networks that financial institutions may not fully appreciate.

As such, many stablecoin issuers typically hold a mix of different assets on top of cash deposits at financial institutions, including short-term US treasuries, commercial paper and other assets of varying liquidity.

It is this demand for a range of financial products that has many financial institutions salivating at the prospect of serving stablecoin issuers as an emerging source for growing fee income.

However, the opportunities provided by stablecoin issuers are not without risk, including idiosyncrasies specific to blockchain networks that financial institutions may not fully appreciate.

One Stablecoin, Many Blockchains

The existence of innumerous blockchain networks complicates monitoring and reporting requirements when it comes to stablecoins.

A stablecoin can exist on multiple blockchain networks and the permissionless nature of public blockchains means issuers have limited (if any) power to censure unsanctioned versions of a stablecoin made for use on other blockchains.

What applies to stablecoins also applies to tokens on different blockchain networks in general.

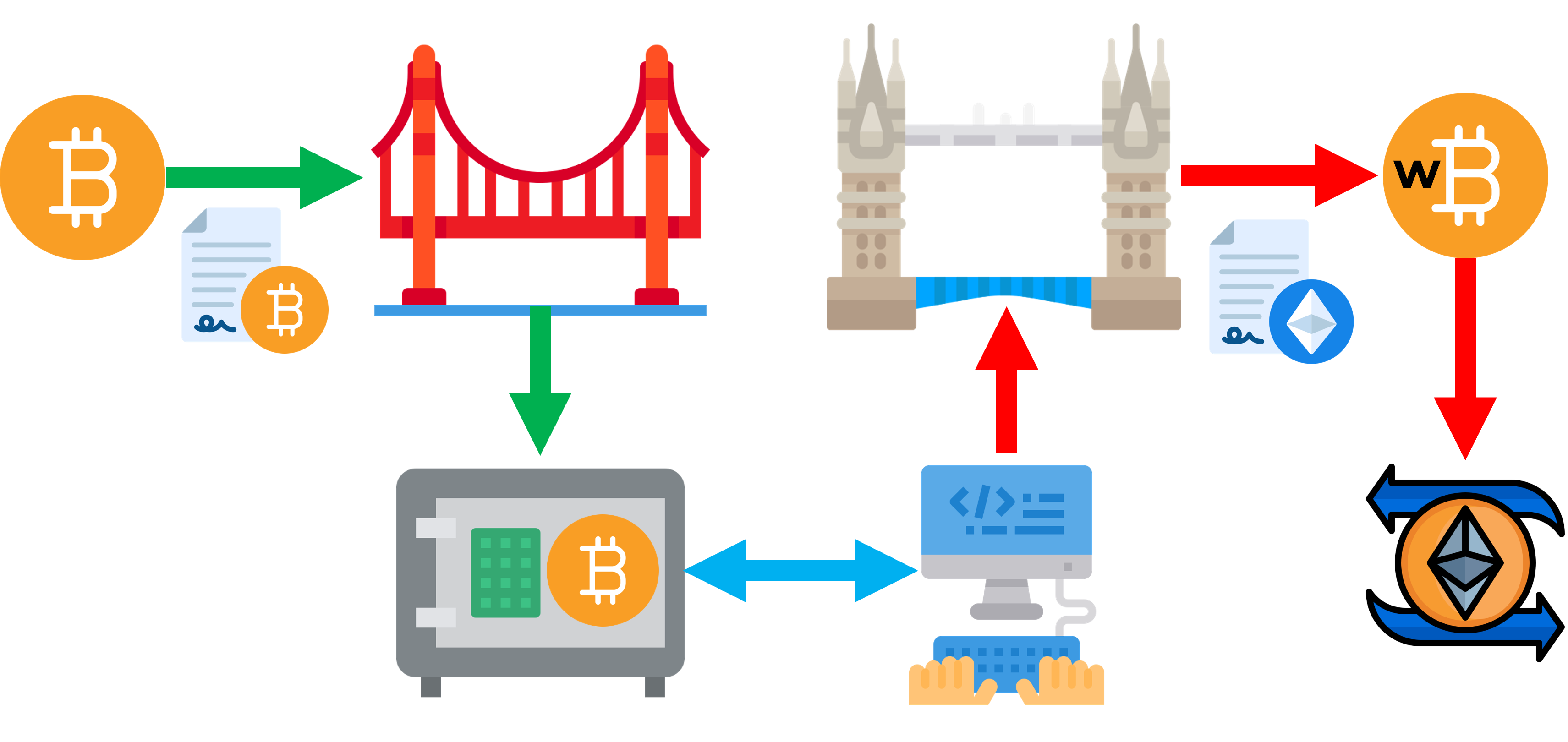

Let’s assume you have some bitcoin, but you’d like to use that bitcoin on the Ethereum blockchain, to make use of Ethereum’s smart contract or DeFi functions.

You can lock your bitcoin on the Bitcoin blockchain with a service provider who will act as a “bridge” to make the equivalent bitcoin available in wrapped form, hence the “w” in front of the bitcoin, as wBTC, minting tokens representing bitcoin on the Ethereum blockchain.

The “wrapped” bitcoin is now usable on the Ethereum blockchain.

You trust the service provider will keep the equivalent of 1:1 backing of the wrapped bitcoin with actual bitcoin in its custody, so that when you need to eventually swap your wBTC for actual bitcoin on the Bitcoin blockchain it is available.

Binance’s BUSD Stablecoin Product

In September 2019, Paxos Trust Company LLC (“Paxos”) a financial institution regulated by the New York Department of Financial Services (“NYDFS”) issued the BUSD stablecoin in collaboration with crypto-asset exchange Binance.

The NYDFS had approved Paxos to issue BUSD on the Ethereum blockchain network, a popular blockchain network favored for its smart contract capabilities.

Paxos issued BUSD on the Ethereum blockchain network, which was the only officially licensed and regulated BUSD product.

However, that didn’t stop Binance from re-issuing a BUSD equivalent product for use on another blockchain network, the BNB Smart Chain (“BSC”).

Blockchain networks are not interoperable, meaning tokens on one blockchain network are not transferable to another without some form of “bridging” exercise.

A “bridge” basically locks tokens on one blockchain network and issues their equivalent tokens for use on another blockchain network.

There are many different bridge designs each with their own trust assumptions, but what they all have in common is that some mechanism exists to relay messages between blockchain networks.

One of the most common methods to “bridge” crypto-assets from one blockchain network to another is through a process called “wrapping.”

A user can deposit their crypto-assets into a smart contract that “locks” their crypto-assets on one blockchain network and a smart contract on a different blockchain network releases a “wrapped” version of that crypto-asset for use.

All bridges require an element of trust in the operator of the bridge and well-established academic research has confirmed that so-called “trustless” bridges do not exist.

Because a bridge is not “trustless”, it is not uncommon for new blockchain networks to operate their own bridges, to provide confidence to users wanting to use the bridge and to hypothecate crypto-assets from an existing blockchain network to the new one, to increase usage.

In the case of Paxos and Binance’s BUSD, to make BUSD available on other blockchain networks such as BSC, Binance “wrapped” BUSD on the Ethereum blockchain network and issued BUSD on the BSC blockchain network.

As with other digital assets, third parties can wrap assets on to other chains. Binance wraps BUSD to issue a pegged version on BNB, BSC, Avalanche and Polygon.

Who’s balancing the books?

The issue with “wrapping” and “bridging” tokens on multiple blockchain networks is keeping track of whether these tokens are appropriately backed one-to-one, a challenge which is especially pertinent to stablecoins.

For instance, it is possible for a “bridge” to issue more tokens on one blockchain network than it has backing those tokens on another blockchain network.

In January 2023, ChainArgos broke the news with Bloomberg that Binance’s BUSD on the BSC blockchain network was unbacked by as much as $1.4 billion dollars at times.

Binance had issued more BUSD on the BSC blockchain network than had been locked in the backing wallet on the Ethereum blockchain network.

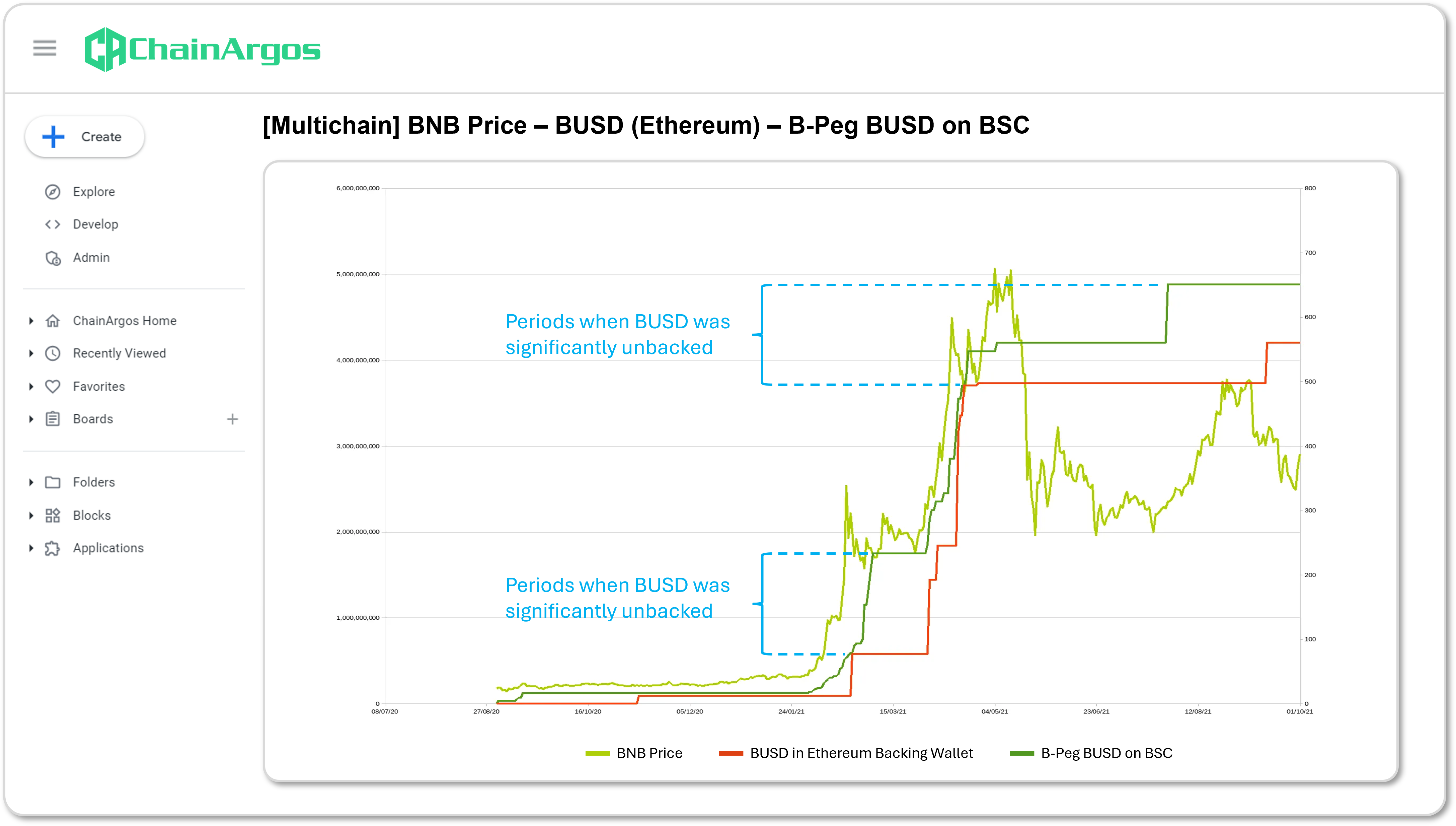

Figure 1. Chart showing time periods when BUSD was unbacked on the BSC blockchain network and the price of the BNB token.

In the chart in Figure 1., the light green line is the price of BNB in dollars, the orange line, the amount of BUSD in the Ethereum blockchain network backing wallet for B-Peg BUSD and the dark green line is the BUSD in circulation on the BSC blockchain network.

BNB is the native token for the BSC blockchain network and the crypto-asset used to receive certain benefits and rewards when using services on Binance.

As can be seen from Figure 1. periods when BUSD on the BSC blockchain network was significantly unbacked occurred just prior to periods where there were significant increases in the price of the BNB token.

The NYDFS acted swiftly in response to the bombshell report by ChainArgos and Bloomberg and by February 2023, ordered Paxos to cease issuance of BUSD on the Ethereum blockchain network, admonishing Paxos for not having adequately supervised its partner Binance.

Binance’s BUSD eventually fell into disuse and is no longer a major stablecoin, but the BUSD stablecoin experience highlights the importance of appropriately monitoring stablecoin circulation.

Monitoring Stablecoin Issuer Activity

For financial institutions looking to provide financial services to stablecoin issuers, understanding how many stablecoins have been minted or burned on a given date is critical.

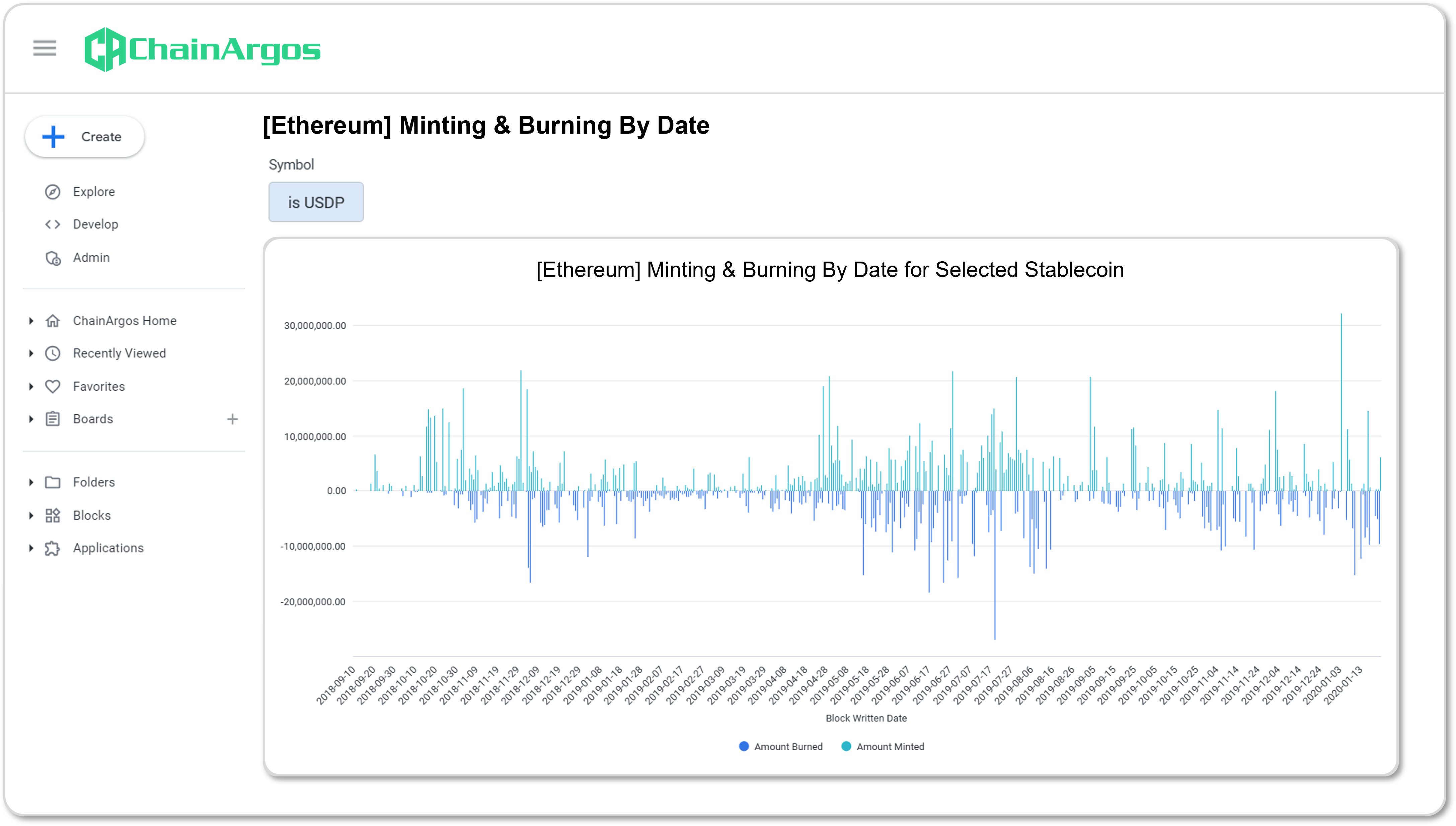

Figure 2. Chart showing the minting and burning of the USDP stablecoin over time.

In Figure 2., the minting and burning of Paxos’ USDP stablecoin over time can be seen in an instant, providing a quick overview of the growth or decline of a stablecoin.

The same dashboard in Figure 2. can be overlaid with multiple stablecoins to determine which stablecoins are growing and which are in decline.

Whether it’s holding cash deposits or short-term government securities for a stablecoin issuer, financial institutions need to understand their stablecoin activity so they can independently verify the economic substance of transactions.

Figure 3. provides the largest minters of the USDC stablecoin over the previous three months and provides unparalleled insight into who are the customers demanding the most stablecoins.

Figure 3. Largest minters of the USDC stablecoin over the previous three months.

In Figure 3., you can see how the biggest minter of USDC is Circle Internet Financial (“Circle”) itself, which makes sense given Circle is the issuer of USDC. However, Circle allows minting of USDC to Circle’s blockchain addresses which are then distributed to customers of Circle.

Figure 4. Largest receivers of the USDC stablecoin over the previous three months from a specific address.

As can be seen from Figure 4., in the case of USDC, the crypto-asset exchanges Coinbase and B2C2 were the primary recipients of USDC in the previous three months.

Not all stablecoin issuers allow minting to the issuer’s blockchain addresses before being handed off to customers. Instead, many stablecoin issuers send freshly minted stablecoins directly to a customer’s blockchain address.

Understanding stablecoin issuance idiosyncrasies helps financial institutions gain a better understanding of the type of transaction behavior to look out for and provide crucial information during stablecoin issuance and redemption exercises.

Knowing who the largest counterparties for a stablecoin are also provides insight into a stablecoin issuer’s main users and counterparties.

It is also possible to analyze the different stablecoins used by a single or cluster of blockchain addresses provided by a customer, to determine whether any regime changes occurred in stablecoin usage.

Figure 5. Stablecoin use for a blockchain address showing different usage patterns across various stablecoins .

As can be seen from Figure 5., the blockchain address being analyzed was a user of the euro-based stablecoin EURC, as well as the dollar-based stablecoins FDUSD, USDC and USDT.

The change in usage patterns of the various stablecoins can be seen in Figure 5. where the blockchain address was initially a heavy user of USDT, before swapping to FDUSD and then later, USDC.

Shifts in stablecoin usage patterns can provide key insight into a customer’s circumstances and enable financial institutions to ask timely questions.

Reconciling Stablecoin Transactions

A major challenge for financial institutions managing assets for stablecoin issuers is independently verifying stablecoin mints and redemptions and determining the identity of counterparties minting or redeeming those stablecoins.

For instance, if a dollar-backed stablecoin issuer claims their customer redeemed stablecoins and requests to transfer the equivalent dollar amount to that customer, how would a bank verify those stablecoins were in fact redeemed by that customer?

Figure 6. Largest redeemers of the USDT stablecoin on the Tron blockchain network over the previous three months.

Figure 6., provides a list of addresses which “burned” or redeemed the Tether stablecoin USDT over the previous three months on the Tron blockchain network, providing both their blockchain addresses and the labels associated with them.

Specific blockchain addresses can also be analyzed to determine if they had indeed “burned” or redeemed stablecoins, consistent with the transactions being contemplated by the financial institution.

Similarly, a financial institution can also see if a fresh deposit of funds by a stablecoin issuer is consistent with the issuance of stablecoins to a specific blockchain address.

The Role of Blockchain Intelligence

Blockchain intelligence plays an important role not just in reconciling on-chain activity with off-chain transactions, but also to ensure financial institutions have an overall understanding of the operating environment for stablecoins.

As more financial institutions embrace crypto-assets, stablecoins and tokenization, access to timely blockchain intelligence is critical to make better informed decisions.

Blockchain intelligence goes well beyond transaction tracing and should provide financial institutions a macro view of the economic purpose behind overall flows.